The Research Phase Grant Writers Can't Afford to Skip

September 14, 2025

Background research is a necessary step in the proposal process. The research produces information that can guide and support the project design while also demonstrating to the donor that the applicant understands the broader context behind the issue the project will address.

In this post, we review what is typically meant by background research. In particular, we discuss what a literature review is in the context of proposal writing and describe a process for conducting one. At the end of the post, you’ll find resources and templates you can adapt and use for your own research needs.

What Background Research Means in the Context of Proposal Writing & Why It Should Be Done

Background research conducted in preparation for writing a grant proposal is similar in many ways to a literature review conducted in an academic context as part of writing a thesis or manuscript. The research goals include learning what is known about a particular topic, such as its history (what research has been done or interventions tried, and how thinking has evolved on an issue) and its status (who is currently working on the topic or issue, and what are the open questions yet to be resolved).

One significant difference between a literature review in academia and background research conducted by a nonprofit in preparation for a grant proposal is that in academia, there is greater emphasis on finding and citing relevant peer-reviewed sources. For proposals, the background research may include peer-reviewed articles, but it will primarily rely on internal project reports and government data as its source material. Proposals written specifically to fund research are an exception, as they follow the academic standard of relying on peer-reviewed sources.

For larger, high-dollar-value proposals, the need for background research — also sometimes referred to by nonprofits as desk research or a literature review — is obvious and may, in fact, be required explicitly by the donor. For other, simpler, or lower-dollar-value proposals, while the donor may not require citations to outside data sources, some external research can still be beneficial.

How to Plan & Conduct Background Research

If you are new to background research or have been left on your own to figure out how to structure your search, consider using the process outlined below, which can be used and adapted by organizations of varying sizes and missions.

Before You Begin Your Research, Know the Questions

Conducting background research for a proposal requires first identifying the questions that need to be answered. The research needs to be focused. Otherwise, you’ll have no idea how to structure the research, such as what source material will be most relevant or what content in those materials will be most useful. Generating the right questions is important because you may not have time to revisit the sources or reinitiate the research once the proposal writing is underway.

Unlike academic literature reviews, the research for a proposal is generally not hypothesis-driven. The questions driving the background research for proposals are targeted toward some aspect of the proposal, such as learning more about the context in which the work will take place or providing ideas for (or evidence supporting) the proposed intervention. The questions should be as specific as possible, as in, “(1) What organizations conducted X-type of programs in X geographic area during the period XXXX to XXXX; (2) what were the key activities and outcomes of this work; and (3) which donors funded this work,” as opposed to “Summarize projects in X geographic area.” Another question could be on strategy, such as “Research successful models of introducing water conservation to smallholder farmers in the following region, with a focus on XYZ areas, summarizing the tools, strategies, target population, benefits/challenges of each model, and the outcomes of the interventions. The cited sources should be within the last five years.”

The questions are central to generating keywords for finding relevant source material. Not every source reviewed will speak to every question, but every source should be relevant in some way to the proposal and its subject matter. Although it isn’t always necessary to have a subject-matter expert conduct the literature review, someone with expertise will be more adept at articulating the “so what” factor — or how the literature supports or undermines the premise of the proposed project — than someone without expertise.

Content Sources: Finding Relevant Literature

For a typical grant proposal focused on project implementation, desk research consists of gathering information from multiple sources, such as:

Recent proposals the organization has submitted, which often include information still relevant and useful for the current proposal.

Recent project reports prepared by the organization. Project reports are particularly valuable if the proposed project is a follow-on project that is a natural progression of the activities covered in the report. Reports on projects conducted in the same geographic or programmatic area are also especially useful.

Reports prepared by other organizations. Topical reports produced by respected national or international organizations, such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the World Health Organization, frequently appear as sources in background research. Reports from peer organizations also fall into this category, especially if the organization has led a precursor project similar to the one being proposed.

Journal articles. As mentioned above, peer-reviewed journal articles are more relevant to certain types of proposals than others. However, as part of the research process, it is always a good idea to check whether there are any recent journal articles (e.g., those published within the last five years) relevant to the context or execution of the proposed project. One limitation of journal articles is that most nonprofits will have difficulty accessing those behind a paywall, though some articles may be available through a local public library.

Government websites. In many countries, government websites — local, regional, and national — can be valuable sources of information, including demographic data, descriptions of agricultural services, economic benchmarks, and educational standards. A caveat with government websites is that they are often outdated. Second, information on government websites can be manipulated to fit political aims and is not always trustworthy.

News outlets. Major newspapers are now mostly, if not entirely, published online, making it easy to incorporate news stories into background research. Like government websites, news outlets are not always objective purveyors of truth. If you choose to include news articles, either stick to respected national or international media outlets or proceed with citing news articles from lesser-known sources, but disclose any known bias or limitations in the reporting.

Miscellaneous websites. Websites of varying degrees of reliability and authority can appear in search results when using a traditional search engine or an AI tool like ChatGPT. These might include the websites of professional associations, nonprofit organizations, or private foundations, which are generally reliable, as well as those of partisan organizations or public figures with extensive followings but limited qualifications and low trustworthiness. As a general rule, it is best to stick to recognized, widely trusted sources. Lesser-known websites can be relevant (e.g., a journalist’s blog). However, if you cite sources that may not be widely known, it is crucial to include a complete citation to the source, which will help reviewers locate the material; if there is space in the proposal, it can also be helpful to provide context about the website’s history and content.

Books. Books are less commonly included in proposal background research, though, depending on the type of funding being sought, the funder, and the subject matter, one or more books may be appropriate. A reason not to cite a book is that it may not be accessible online, which can be an obstacle for easily documenting content or, for the proposal reviewer, accessing the book’s content to verify a citation.

Organizing Your Research

Background research can be organized in different ways. The appropriate format or approach depends on the type of research and the preferences of both the team and the researcher. A few options include:

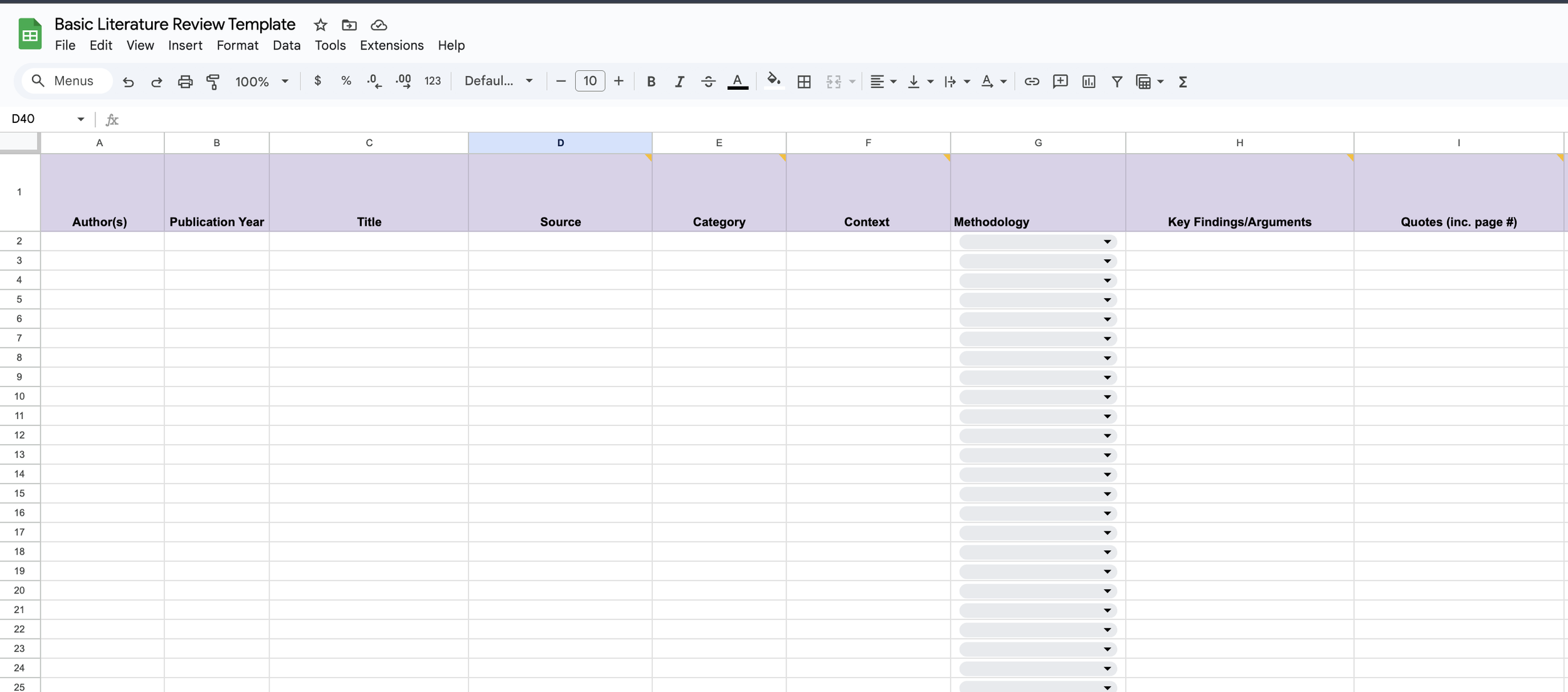

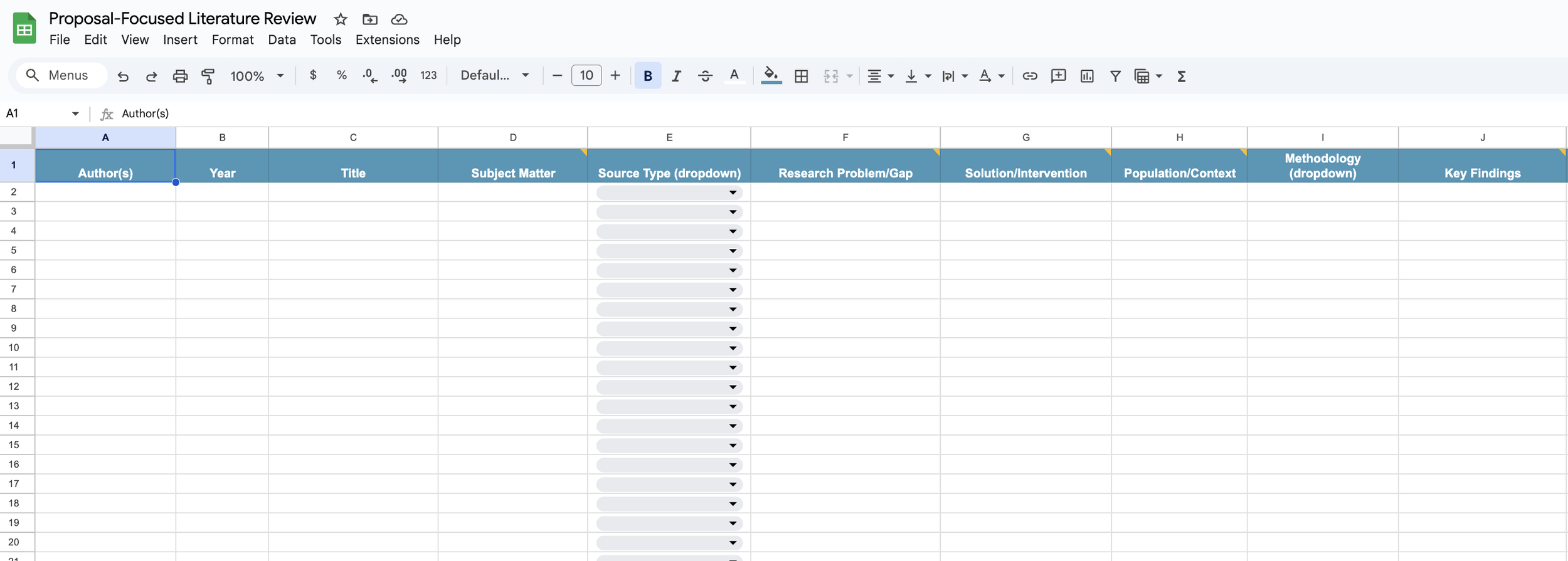

A spreadsheet. The spreadsheet model is the most common format for academic literature reviews and can also work well for background research in proposals. The advantage of a spreadsheet is that it is easy to scan. The challenge with using spreadsheets is that they can encourage overly brief responses, which may fail to provide the proposal writer with enough information. Additionally, in our experience, there’s a tendency to leave most of the cells blank. Leaving the occasional cell blank is fine — not every column will be relevant for every source — but if too much of the spreadsheet is left blank, the literature review will offer limited value.

→ For reference, two spreadsheet templates are provided below, which you can download and tailor to your needs by deleting or renaming columns. In the spreadsheets, we’ve tagged several column headings with comments to explain what type of information belongs in the column.

A wiki tool. Another option, used less commonly but useful in some circumstances, is a wiki tool like Notion, Slab, or Microsoft Loop, which can be used to create a shared knowledge base. The benefits of wikis are that (1) you can use them to share information in a document format or as a spreadsheet, and (2) information added to a wiki is easy to share and co-edit, allowing it to be continually updated for new opportunities. As an example, we’ve created a Notion version of a literature review template (click the image below to view and duplicate the template into your Notion account). One negative of a wiki is that, while it is easy to share a literature review as a page or series of interconnected pages, it is not always as easy to download the content and share it as an editable file. However, both Notion and Loop offer this functionality. With Notion, you can export your spreadsheet as a CSV. Loop integrates with other Microsoft tools, allowing any Loop table to be exported to Excel.

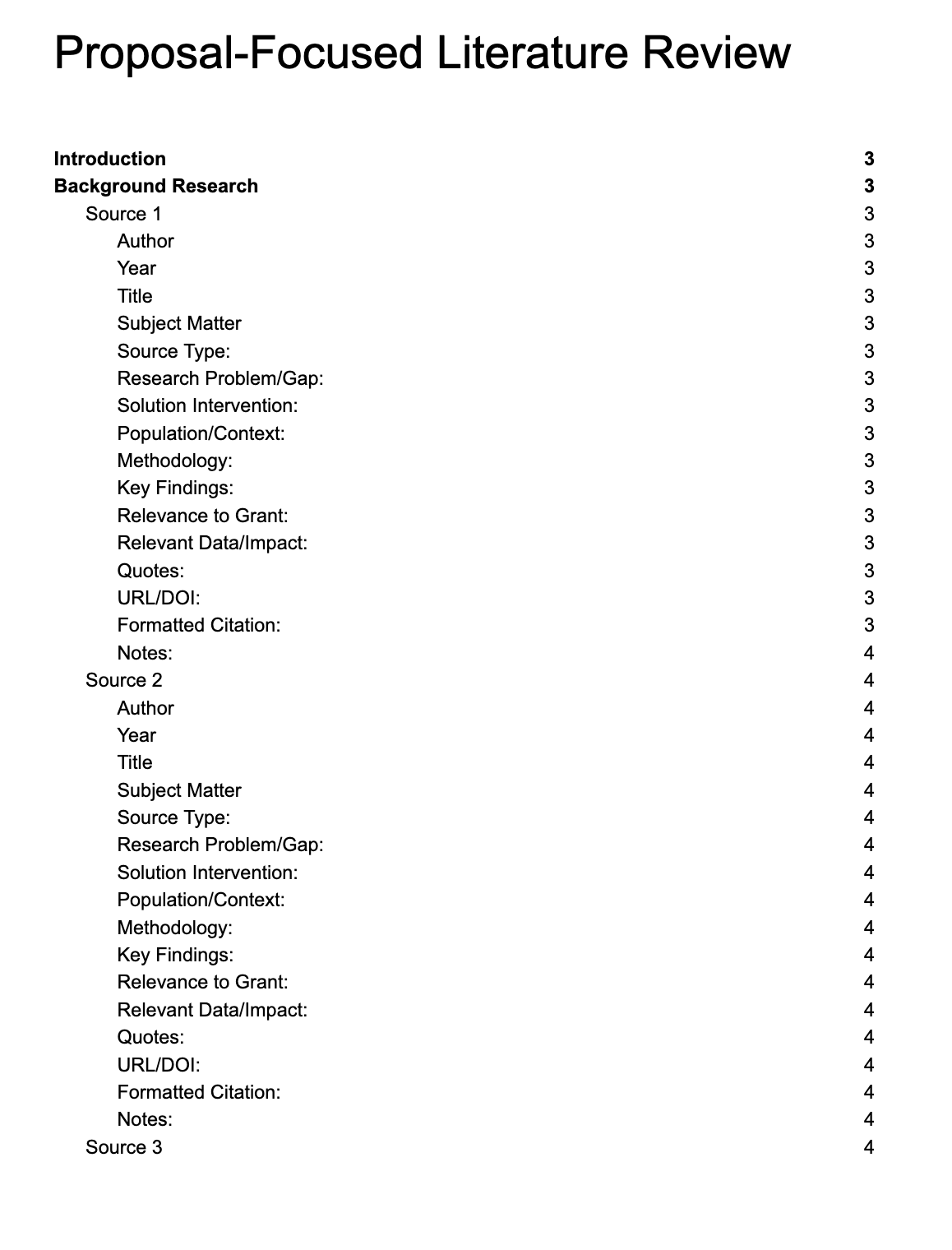

Document format. You can also organize your research as a Word file or a Google Doc. If you decide to go this route, it is important to develop a template to ensure that you capture similar types and amounts of information about each source. If you have a template formatted correctly with different style settings for each heading level, you can automatically generate a table of contents, making the document easier to navigate. One note of caution about using a document format is that it can be tempting to fall into a “book report” mode of stating what a source document is about instead of analyzing the content and focusing the summary on how (and how well) the content in the literature relates to the subject matter of your proposal.

On the other hand, one advantage of a document format, and why some people prefer it over a spreadsheet, is that having key findings from desk research already written up in long form (versus the typically truncated form found in spreadsheets) can facilitate the proposal writing process. This is because some of the summary information and analysis from the literature review may be written in a way that can be imported into the proposal as-is or with relatively minor edits.

→ For an example of a document-based template for background research, we’ve created an example in Google Docs that you can view, download, and customize to fit your needs. You can find the template below in the list of downloads.

A Less Common Step for Proposals: Writing a Formal Literature Review

In an academic setting, the information captured in your notes (i.e., the document file or spreadsheet format described earlier) would be used to write a document that organizes the literature according to a particular structure, which could be chronologically, thematically, or by methodology or publication. The goal of the document is to synthesize the information and draw conclusions about what the literature as a whole is saying relative to the chosen topic.

A basic structure for a typical literature review is: introduction (what the topic is and its relevance), the body (critical analysis of each source and how it relates to your topic), and conclusion (summary of key findings, areas of agreement or disagreement in the literature, and identified gaps for further research).

For proposal writing, although the term “literature review” is sometimes used to refer to background or desk research in preparation for writing a proposal, this step of actually writing a literature review is almost never done. When someone at a nonprofit requests that someone complete a literature review, they are almost always referring only to the initial work of conducting background research and preparing notes in the form of a spreadsheet or Word document. They rarely expect a literature review in the sense of a formal write-up. One important exception is research proposals.

For research proposals, a literature review section is typically a required section within the proposal. However, it is an abbreviated version constrained by page limits and usually does not follow the formal outline provided above, which includes an introduction and conclusion. Instead, it might be a page of dense text, listing several highly relevant peer-reviewed journal articles and highlighting their key points, contributions to the field, and their gaps. Pointing out the gaps in the literature is essential in research proposals because the proposed research must be positioned as filling a knowledge gap left unaddressed by prior research.

→ For a basic literature review template, you can view, download, and edit the one we’ve created in Google Docs by clicking on the image below.

Additional Tips for Conducting Background Research

As part of defining the scope of the review, there should be limits on the age of the material being reviewed. For example, it is common for literature reviews to only include materials published within the last five years.

Regarding the chosen format for organizing the research — narrative document, spreadsheet, or wiki — it is crucial to list the complete citation for the source. Ideally, the reference should be formatted in the style used by the organization or required by the donor (e.g., American Psychological Association) because formatting citations after they’ve been inserted into the proposal can be a significant burden to the proposal writer or editor.

To make it easier for the rest of the proposal team to find and verify information in the cited materials, include relevant page numbers.

Journal articles, reports, and other documents (unless confidential) included in the background research should be uploaded into a shared folder or a reference manager, such as Mendeley, so that the entire proposal team can refer to them if necessary. For more information on Mendeley, see our post on using reference managers.

Summary

Background research, also known as desk research or literature review, is an essential preliminary step in preparing proposals. The research should start by defining the questions that need to be answered, such as learning about the context in which the proposed project will take place, or whether there is any evidence to support the proposed project design. The questions focus the research by helping to identify keywords, which point the way regarding where to look for relevant resources, such as reports, proposals, journal articles, and trusted news sources.

Literature reviews are more than simply copying and pasting information from the source material. As you review articles, reports, websites, and other materials, you should actively engage with the material so that you can spot answers to the questions you’ve generate in the first step in the process: In completing the literature review, you are filling your knowledge gaps so that you can accurately write about the context of the project and looking for gaps in knowledge so that you can position your project to address them.

Conducting background research can be a time-consuming process. If you know you’ll be working on a proposal on a particular topic in the near future, it’s a good idea to go ahead and start the research process by creating a preliminary list of keywords, identifying and gathering what you believe will be relevant internal documents, and searching for relevant external literature. After the solicitation is released, you can then revisit the literature review research summary and determine if it needs to be updated.

Downloads

Click on each image to open and download the file.

Background research is a necessary step in the proposal process. The research produces information that can guide and support the project design while also demonstrating to the donor that the applicant has an understanding of the broader context behind the issue the project will address.

In this post, we review what is typically meant by background research. In particular, we discuss what is meant by a literature review in the context of proposal writing and describe a process for conducting it. At the end of the post, you’ll find resources and templates you can adapt and use for your own research needs.